Branches

draped down. Mud squished underfoot. A cloud of mosquitoes rose

to the feast. The men stepped past discarded gas-mask filters

to the entrance of a ghostly kindergarten. They fanned out with

cameras, to work.

Branches

draped down. Mud squished underfoot. A cloud of mosquitoes rose

to the feast. The men stepped past discarded gas-mask filters

to the entrance of a ghostly kindergarten. They fanned out with

cameras, to work.

L'Express, 4/7/2005:

C'est le dernier spot à la mode des

touristes branchés: Tchernobyl, en Ukraine. Le site de

la plus grande catastrophe nucléaire civile de tous les

temps est en principe fermé au public, mais l'agence d'information

Chernobylinterform a obtenu depuis quelques mois l'autorisation

d'organiser des excursions en groupe dans la zone interdite. L'organisme

affirme que la radioactivité n'est pas dangereuse pour

la santé, «du moins à court terme» et

à condition de se plier à quelques recommandations:

toujours rester sur le béton, ne prendre aucun objet, éviter

le contact avec les mousses et les lichens, où se concentrent

les isotopes. Près d'un millier de curieux venus de tous

les continents - américains, suédois, japonais,

français ou chinois - ont embarqué l'an dernier

pour la visite guidée d'une journée, facturée

entre 200 et 400 dollars.

Au programme, les rues désertes de la ville fantôme

de Pripyat, vidée de ses habitants depuis 1986, le cimetière

de camions et d'hélicoptères contaminés qui

ont servi à nettoyer le site et, bien sûr, une tour

de la centrale dévastée recouverte de son sarcophage.

On trouve parmi ces touristes intrépides une clientèle

inattendue: celle d'écologistes et d'ornithologues venus

admirer la faune. Les forêts ont repoussé et les

animaux sont revenus dans cette zone débarrassée

de toute présence humaine, où pullulent les loups,

les sangliers et les espèces d'oiseaux rares...

Gilbert Charles

The New York Times, June 15, 2005:

PRIPYAT, Ukraine, June 11 - Sometime after visiting the ruins of the Polissia Hotel, the darkened Energetic theater and the idled Ferris wheel, the minivans stopped again. Doors slid open. Six young Finnish men stepped out and followed their guide through a patch of temperate jungle that once was an urban courtyard.

Branches

draped down. Mud squished underfoot. A cloud of mosquitoes rose

to the feast. The men stepped past discarded gas-mask filters

to the entrance of a ghostly kindergarten. They fanned out with

cameras, to work.

Branches

draped down. Mud squished underfoot. A cloud of mosquitoes rose

to the feast. The men stepped past discarded gas-mask filters

to the entrance of a ghostly kindergarten. They fanned out with

cameras, to work.

Much was as the children and their teachers had left it 19 years ago. Tiny shoes littered the classroom floor. Dolls and wooden blocks remained on shelves. Soviet slogans exhorted children to study, to exercise, to prepare for a life of work.

Much had also changed. Now there is rot, broken windows, rusting bed frames and paint falling away in great blisters and peels. And now there are tourists, participating in what may be the strangest vacation excursion available in the former Soviet space: the packaged tour of the Chernobyl exclusion zone, scene of the worst civilian disaster of the nuclear age.

A 19-mile radius around the infamous power plant, the zone has largely been closed to the world since Chernobyl's Reactor No. 4 exploded on April 26, 1986, sending people to flight and exposing the Communist Party as an institution wormy with hypocrisy and lies.

For nearly 20 years it has been a dark symbol of Soviet rule. Its name conjures memories of incompetence, horror, contamination, escape and sickness, as well as the party elite's disdain for Soviet citizens, who were called to parade in fallout on May Day while the leaders' families secretly fled.

Now it is a destination, luring people in. "It is amazing," said Ilkka Jahnukainen, 22, as he wandered the empty city here that housed the plant's workers and families, roughly 45,000 people in all. "So dreamlike and silent."

The word Chernobyl also long ago became a dreary, shopworn joke, shorthand for contaminated wasteland. But Chernobylinterinform, the zone's information agency, says its chaperoned tours do not carry health risks.

This is because, the agency says, radiation levels here have always been uneven. And most of the zone is far cleaner than it was in 1986, when radiation levels were strong enough in places to kill even trees.

A lethal exposure of radiation ranges from 300 to 500 roentgens an hour; levels in the tour areas vary from 15 to several hundred microroentgens an hour. A microroentgen is one-millionth of a roentgen. Dangers at these levels, the agency says, lie in long-term exposure.

Still,

the zone in northern Ukraine has much more radioactive spots than

those where tourists typically go. So there are rules, which Yuriy

Tatarchuk, a government interpreter who served as the Finns' guide,

listed.

Still,

the zone in northern Ukraine has much more radioactive spots than

those where tourists typically go. So there are rules, which Yuriy

Tatarchuk, a government interpreter who served as the Finns' guide,

listed.

Don't stray. Stay on concrete and asphalt, where exposure risks are lower than on soil. Don't touch anything. (This one proved impossible. Tours involve climbing cluttered staircases and stepping through debris. Handholds are inevitable.)

No matter its inconveniences or potential for medical worry, the zone possesses the allure of the forbidden and a promise of rare, personal insights into history. Its popularity as a destination is increasing. Few tourists came in 2002, the year it opened for such visits, according to Marina Polyakova, of Chernobylinterinform. In 2004 about 870 arrived, she said, a pace tourists are matching this year.

Tourists cannot wander the zone on their own. One-day group excursions cost $200 to $400, including transportation and a meal.

The tour on Saturday began with a drive through meadows, marshes and forest, belts of green broken by glimpses of gap-roofed houses and crumbling barns.

It is what Mary Mycio, a Ukrainian-American lawyer in Kiev and author of a soon-to-be released book, "Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl," calls a "radioactive wilderness," an accidental sanctuary populated by wolves, boars and endangered birds. Its beauty cannot be overstated.

Soon reminders of the grim history appeared. The tour stopped at a graveyard of vehicles and helicopters used to fight Chernobyl's fires.

Roughly 2,000 radioactive machines are parked here - fire trucks, ambulances, armored vehicles, trucks, aircraft. Two tourists slipped through the barbed wire and wandered the junkyard, taking pictures for a Web site they plan to make of the trip. The rest roamed the edge, awed. "I cannot find words," said Juha Vaittinen, 22.

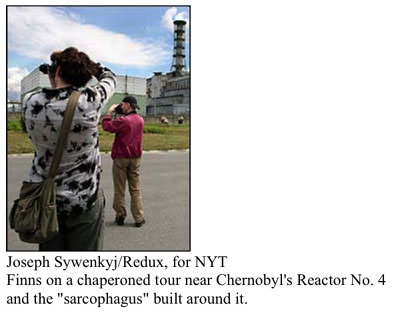

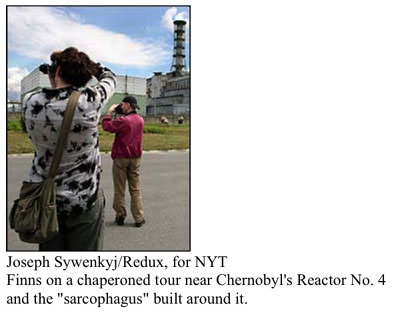

The minivans then headed to Chernobyl proper for a briefing on the accident. Next stop: the nuclear plant and "sarcophagus," the concrete-and-steel shell built to contain Reactor No. 4's radioactive spew. Mr. Tatarchuk held up a radiation detector - 470 microroentgens per hour.

The Finns posed for a group shot.

Motivations for coming here are many. The Finnish tourists, all in their 20's, said they had an affinity for lonely, abandoned places, and the zone so far exceeded the forgotten homes, farms or industrial spaces in Finland that its draw became irresistible. They flew to Kiev from Helsinki solely for the trip.

Mr. Tatarchuk said others had turned up because they were curious about the disaster, or wished to enter an accidental preserve of Soviet life. Bird-watchers have visited to catalogue the zone's resurgent life.

One group came for a hoax. About two years ago, Mr. Tatarchuk said, a Ukrainian woman booked a tour, wore a leather biker jacket and posed for pictures. Soon there appeared a Web site in which the woman, using the name Elena, claimed that she had been given an unlimited pass by her father, a nuclear physicist and Chernobyl researcher ("Thank you, Daddy!" she wrote) and now roamed the ruins at will on her Kawasaki Big Ninja.

The site, www.kiddofspeed.com, billed as a tale "where one can ride with no stoplights, no police, no danger to hit some cage or some dog," was a sensation, duping uncountable viewers before being discredited.

The Finns said they had seen the Web site, and hoped their planned site would be as popular.

On the day of their tour, the most haunting destination came last: Pripyat, a city left behind. "Heralded as the world's youngest city when it opened its doors in the mid-1970's," Ms. Mycio writes, "Pripyat also turned out to be its shortest lived."

The city was encased on this day in a silence broken by breezes sighing through rustling trees. A heavier hush resided in buildings, where drops of water plopped loudly into puddles, and glass squeaked as it broke underfoot. Built on marshes, the place smelled of peat.

At the amusement park, near idled bumper cars, Mr. Tatarchuk's monitor registered 144 microroentgens an hour. He moved four feet away, to a mat of damp green moss. It read 823. "Stay off the moss," he said.

The moss is all around. Pripyat, both a time capsule of the Soviet Union and a monument to its folly and pain, is being consumed. What looters have not sacked or stolen succumbs now to the elements and time.

A cafe patio atop the Polissia Hotel, offering views to the reactor that ruined this place, has been colonized by birch trees. One stands roughly seven feet tall, climbing skyward from a crack in the high-rise's tiles.

Fine views of Pripyat are available from among these misplaced trees, including one in the direction of the reactor that reveals an empty clinic bearing an enormous sign. "The health of the people," it reads, "is the wealth of the country."

Mr. Tatarchuk, looking down over buckling rooftops, repeated those words in Russian, then allowed himself a knowing, head-shaking smile.

C. J. CHIVERS

Le Monde, 30/1/02:

Envie de vacances ? Lassés des traditionnelles destinations touristiques, du bronzage en Martinique ou des balades sur les canaux de Venise ? Il existe maintenant une alternative particulièrement chaude que le Sunday Herald s'est empressé de relater. New Men Travel, une agence touristique de Kiev, en Ukraine, propose de visiter la centrale de Tchernobyl, dont l'un des réacteurs a explosé le 26 avril 1986, provoquant la plus grande catastrophe nucléaire de tous les temps.

Rassurez-vous, compteurs Geiger et combinaisons de protection sont fournis. Le prix du frisson est de 460 dollars pour un tour des vestiges les plus dangereux du site contaminé, en voiture privée et accompagné d'un guide parlant l'anglais. Il en coûtera 340 dollars pour un tour en minibus. Plus collectif, il permet aussi de partager angoisses et appréhensions.

L'agence a tout prévu : cinq itinéraires sont proposés. Ils commencent tous dans la zone d'exclusion, un cercle de sécurité de 30 km autour de la centrale. La visite de base comprend la présentation d'une maquette de Tchernobyl et se conclut par quelques minutes sur un balcon avec vue sur le sarcophage qui recouvre le bloc-réacteur numéro 4 de la centrale. Pour les amateurs de ville fantôme, un tour dans la ville de Pripiat, qui jouxte la centrale, est proposé. Impression inoubliable et solitude garantie : les 50 000 habitants ont été évacués. Pour ceux qui en veulent plus, New Men Travel offre des services particuliers. Certains itinéraires promettent, par exemple, de visiter le cimetière des déchets de la catastrophe. Pour ceux qui ont un fort appétit, Dimitri Osyka, directeur de l'agence, organise des repas à la centrale.

Le coût des visites est en réalité beaucoup plus élevé que ne l'annonce l'agence touristique. Un an après la fermeture définitive de la centrale de Tchernobyl, celle-ci reste toujours une sérieuse menace. Shaun Burnie, un activiste qui a participé aux campagnes antinucléaires de Greenpeace et qui a visité la centrale, n'en recommande pas la visite "Chaque personne qui se rend (sur le site) prend un risque", rapporte le Sunday Herald.

Malgré une aide de 2,3 milliards de dollars (2,6 milliards d'euros) fournie par l'Occident à Kiev pour sécuriser le site, à tout moment, le sarcophage, monté à la va-vite après la tragédie, menace de s'effondrer et de libérer à l'air libre un magma hautement radioactif de 160 tonnes. La radioactivité qui continue à s'échapper des failles du monstre nucléaire a déjà provoqué une épidémie de cancers de la thyroïde en Ukraine et en Biélorussie.

Ceux qui souhaiteraient toutefois se frotter à l'atome peuvent contempler à moindre risque, depuis l'autoroute du Soleil, l'imposante centrale nucléaire de Cruas-Meysse, qui, elle, est fiable nous assure EDF.

Edouard Pflimlin